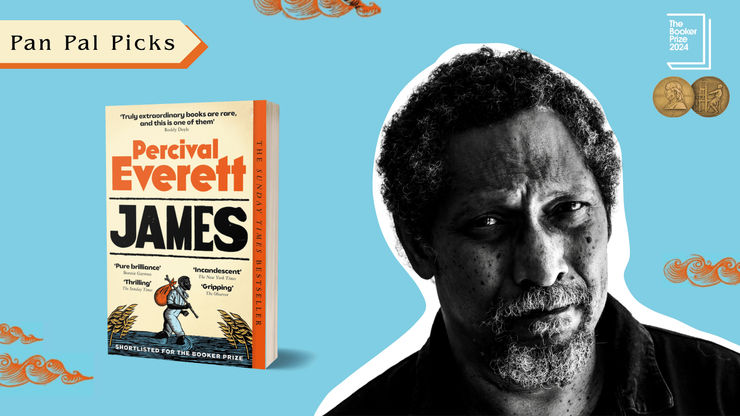

Is James by Percival Everett the Best Novel of 2024—and a Future Classic?

After snagging the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2025 and making the illustrious Booker Prize shortlist in 2024, it's safe to say that Everett's narrative has captured the imagination of readers and critics alike, reinforcing its place as a contemporary classic.

Lopamudra Nayak, a reader from our community, shares her thoughts on this remarkable book.

I don’t say this lightly—James by Percival Everett might be one of the most powerful works of fiction I’ve read in recent years. It’s a novel that doesn’t just reimagine The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; it completely reframes it, excavating everything that was left unsaid in Twain’s original and giving full, resonant voice to the man at its periphery: Jim. Or rather, as Everett insists we finally call him, James.

For context, Everett is no stranger to intellectual fiction. His previous novels have ranged from philosophical to absurdist to deeply political. But James is his most accessible and affecting work yet—urgent without being heavy-handed, deeply intelligent without sacrificing narrative propulsion. It’s a novel with bite, but more importantly, one with heart.

One of the most striking aspects of James is how vividly human the titular character becomes. Everett doesn’t flatten James into a symbol of virtue or stoicism. Instead, he gives us someone full of contradictions: cautious and quick-witted, angry and compassionate, weary but always aware. The James we meet here is literate (in secret), well-read (dangerously so), and endlessly reflective. His mind is constantly in motion—even as his body is enslaved, his thoughts roam through Rousseau, Locke, and Voltaire. He learns in the shadows, at great cost. In one of the most painful moments in the book, a fellow enslaved man is lynched for simply providing him with a pencil stub.

Here’s a theory I keep returning to, especially after rereading the novel multiple times: Everett’s James feels like a fictional incarnation of James Baldwin. It’s not just the name—though that alone invites consideration—but the presence, the intelligence, and the internal clarity James exudes. Like Baldwin, he wields language with precision, not just to survive but to bear witness. I often pictured Baldwin as I read, particularly the Baldwin of the 1965 Cambridge Union debate—eloquent, composed, and yet vibrating with contained fury at the injustice of it all. Everett’s James channels that same quiet defiance. There’s a moment late in the book where he, for the first time, is allowed to look his oppressors directly in the eye. It reminded me of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s line in Between the World and Me, a tribute to Baldwin in many ways, where he writes that slavery is not “an indefinable mass of flesh” but “a particular, specific enslaved woman, whose mind is as active as your own.” Everett more than lives up to that prescription, imagining James not as an archetype, but as a particular, richly alive individual whose inner life is as urgent and complex as any in literature.

The way Everett navigates voice and language is particularly impressive. Because James must code-switch for survival, he adopts what he calls his “slave filter,” reducing his speech in front of white people to caricature. He uses this as both armour and weapon. Everett plays with this duality constantly—how the same mind that can analyse irony or understand a hypotenuse must outwardly pretend not to grasp basic English. The performance is exhausting, and it shows.

The novel follows much of Twain’s original structure: James is on the run after hearing that Miss Watson plans to sell him to a man in New Orleans. Huck, having faked his own death, is on the run too. Their paths converge on an island, and the journey down the Mississippi begins. Familiar set pieces appear—the fog-induced separation, the ridiculous con artists, Huck’s cross-dressing disguise. But Everett shifts the timeline slightly, dropping us closer to the Civil War, with the faint sound of Union boots somewhere in the background.

Where Everett departs significantly is in how he inserts moments of stunning satire and insight. The most unforgettable scene involves James being forced to join a blackface minstrel troupe—the Virginia Minstrels—as their lead tenor. Because no Black man can appear onstage, James must apply blackface himself. The scene is grotesque, absurd, and deeply unsettling: a light-skinned Black man painting his face to look like a white man pretending to be Black. It’s both a surreal performance and a damning commentary on performance itself—on how Blackness has been historically commodified and distorted.

‘This isn’t just a retelling for retelling’s sake. James interrogates the American mythos at every level. It challenges the moral simplicity of Twain’s story. Huck is still here, but the emotional weight has shifted. This time, the pain is James’s. The choices are James’s. The consequences fall, as they always have, disproportionately on James.’

And that’s what elevates this novel. Everett isn’t interested in nostalgia or homage. He’s writing a literary corrective—one that doesn’t just revise the canon but critiques the conditions that made the original possible. Like Jean Rhys did in Wide Sargasso Sea or Kamel Daoud in The Meursault Investigation, Everett pulls a marginalised character out of the margins and allows them to take up the space they always deserved.

In my opinion, James stands firmly alongside the best modern retellings. Like Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver, you don’t need to read the original to appreciate it—but once you do finish Everett’s novel, I’d be surprised if you didn’t feel curious about Twain’s. That said, I suspect your view of it will be irrevocably changed.

This book doesn’t seek to make you comfortable. It asks you to look again—at history, at language, at whose story gets told and how. It’s compelling, sharp, and surprisingly moving. I’ve already reread it, and I don’t doubt I will again.

James

by Percival Everett

A 'Book of the Year' in The Observer, The Times & Sunday Times, The Guardian, Daily Mail, Daily Express, The Spectator, New Statesman, Independent, TLS, The Daily Telegraph, Financial Times, i newspaper, The Economist, The Irish Times, The New York Times, TIME and The New Yorker

'Who should read this book? Every single person in the country' – Ann Patchett

'My favourite novel this year' – Salman Rushdie